One test commonly done during design validation of

handheld battery powered devices is to evaluate their ability to withstand a

short loss of battery power due to being bumped and the contacts momentarily

bouncing open, and either remain operating or have sufficient time to handle a shutdown

gracefully. The duration of a contact bounce can typically range anywhere from

under a millisecond to up to 100 milliseconds long.

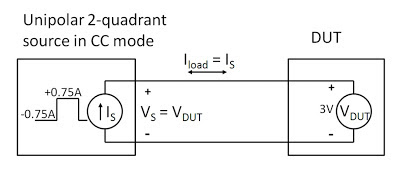

To simulate battery contact bouncing one may consider

programming a voltage drop out on a reasonably fast power supply with arbitrary

waveform capabilities, like several of the N675xA, N676xA, or N678xA series

modules used in the N6700 series Modular DC Power System or N6705B DC Power

Analyzer mainframe, shown in Figure 1. It is a simple matter to program a

voltage dropout of specified duration. As an example a voltage dropout was

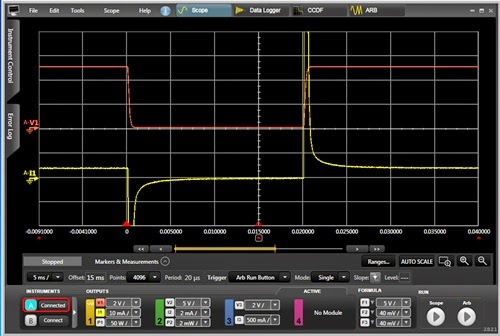

programmed in Figure 2 on an N6781A SMU module using the companion 14585A

software.

Figure 2: Programming a voltage drop out using the N6705B

and N6781A SMU module

While a voltage dropout is fine for many applications,

like automotive, in many situations it does not work well for simulating

battery contact bounce. The reason for this is there is one key difference to

note about a voltage dropout versus a battery contact bounce. During a voltage

dropout the source impedance remains low. During a battery contact bounce the

source impedance is an open circuit. However, a DC source having the ability to

generate a fast voltage dropout is a result of it being able to pull its output

voltage down quickly. This is due to its ability to sink current as well as

source current. The problem with this is, for many battery powered devices,

this effectively short-circuits the battery input terminals, more than likely

causing the device to instantly shut down by discharging any carry-over storage

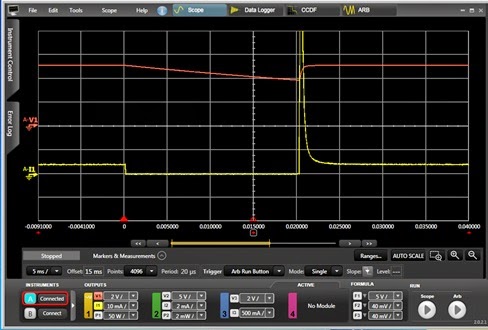

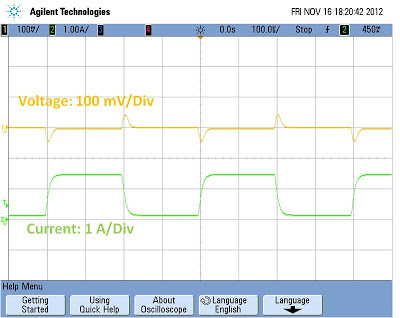

and/or disrupting the battery power management system. As one example consider

a mobile device having 50 microfarads of input capacitance and draws 4

milliamps of standby current. This capacitance would provide more than adequate

carryover for a 20 millisecond battery contact bounce. However, if a voltage

dropout is used to simulate battery contact bounce, it immediately discharges

the mobile device’s input capacitance and pulls the battery input voltage down

to zero, as shown by the red voltage trace in Figure 3. The yellow trace is the

corresponding current drain. Note the large peaks of current drawn that

discharge and recharge the DUT’s input capacitor.

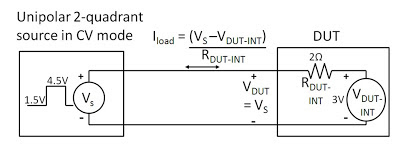

One effective solution for preventing the DC source from

shorting out the battery input is to add a DC blocking diode in series with the

battery input, so that current cannot flow back out, creating high impedance

during the dropout. This is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Blocking diode added between SMU and DUT

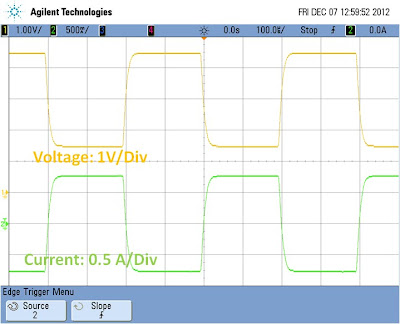

One thing to note here is the diode’s forward voltage

drop needs to be compensated for. Usually the best way to do this just program

the DC source with the additional voltage needed to offset the diode’s voltage

drop. The result of this is shown in Figure 5. As shown by the red trace the

voltage holds up relatively well during the contact bounce period. Because the

N6781A SMU has an auxiliary voltage measurement input it is able to directly

measure the voltage at the DUT, on the other side of the blocking diode,

instead of the output voltage of the N6781A. As seen by the yellow current

trace there is no longer a large peak of current discharging the capacitor due

to the action of the blocking diode.

Now you should have a much better appreciation of the

differences between creating a voltage dropout and simulating battery contact

bounce! And as can be seen a blocking diode is a rather effective means of

simulating battery contact bounce using a voltage dropout. Stay tuned for my

second part on additional ways of simulating battery contact bounce on an

upcoming posting.

.