Two years ago I added a post here to “Watt’s Up?”

titled: “Zero-burden ammeter improves battery run-down and charge

management testing of battery-powered devices” (click here to review). In this

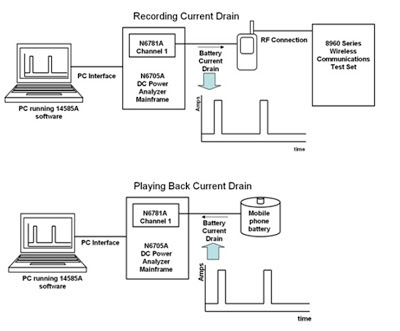

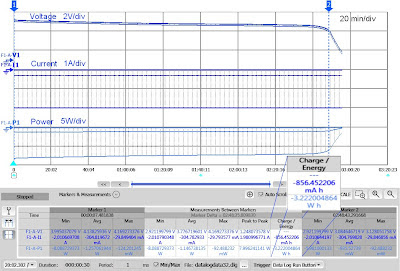

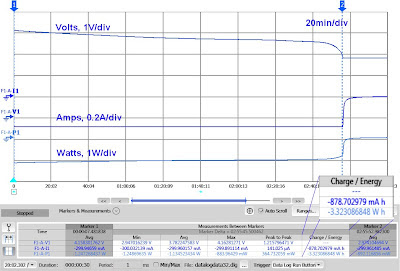

post I talk about how our N6781A 20V, 3A 20W SMU (and now our N6785A 20V, 8A,

80W as well) can be used in a zero-burden ammeter mode to provide accurate

current measurement without introducing any voltage drop. Together with the

independent DVM voltage measurement input they can be used to simultaneously

log the voltage and current when performing a battery run-down test on a

battery powered device. This is a very useful test to perform for gaining

valuable insights on evaluating and optimizing battery life. This can also be

used to evaluate the charging process as well, when using rechargeable

batteries. The key thing is zero-burden current measurement is critical for obtaining

accurate results as impedance and corresponding voltage drop when using a

current shunt influences test results. For reference the N678xA SMUs are used

in either the N6705B DC Power Analyzer mainframe or N6700 series Modular Power

System mainframe.

There

are a few considerations for getting optimum performance when using the N678xA

SMU’s in zero-burden current measurement mode. The primary one is the way the

wiring is set up between the DUT, its battery, and the N678xA SMU. In Figure 1

below I rearranged the diagram depicting the setup in my original blog posting

to better illustrate the actual physical setup for optimum performance.

Figure

1: Battery run-down setup for optimum performance

Note that

this makes things practical from the perspective that the DUT and its battery

do not have to be located right at the N678xA SMU. However it is important that the DUT and

battery need to be kept close together in order to minimize wiring length and associated

impedance between them. Not only does the wiring contribute resistance, but its

inductance can prevent operating the N678xA at a higher bandwidth setting for

improved transient voltage response. The reason for this is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Figure

2: Load impedance seen across N678xA SMU output for battery run-down setup

The

load impedance the N678xA SMU sees across its output is the summation of the

series connection of the DUT’s battery input port (primarily capacitive), the

battery (series resistance and capacitance), and the jumper wire between the

DUT and battery (inductive). The N678xA SMUs have multiple bandwidth

compensation modes. They can be operated in their default low bandwidth mode,

which provides stable operation for most any load impedance condition. However

to get the most optimum voltage transient response it is better to operate

N678xA SMUs in one of its higher bandwidth settings. In order to operate in one

of the higher bandwidth settings, the N678xA SMUs need to see primarily

capacitive loading across its remote sense point for fast and stable operation.

This means the jumper wire between the DUT and battery must be kept short to

minimize its inductance. Often this is all that is needed. If this is not

enough then adding a small capacitor of around 10 microfarads, across the

remote sense point, will provide sufficient capacitive loading for fast and

stable operation. Additional things that should be done include:

- Place remote sense connections as close to the DUT and battery as practical

- Use twisted pair wiring; one pair for the force leads and a second pair for the remote sense leads, for the connections from the N678xA SMU to the DUT and its battery

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)