In some of my previous posts I have talked about USB

power delivery 2.0 providing greater power so that mobile devices can be

charged up more quickly with their USB adapters. A key part of this is these devices are

incorporating adaptive fast charging systems to accomplish faster charging. So

how does this all work anyway?

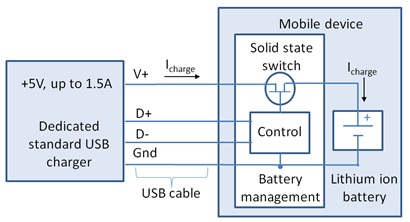

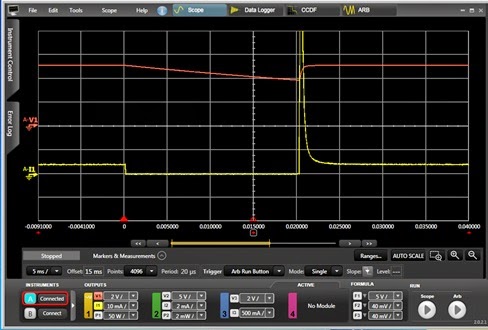

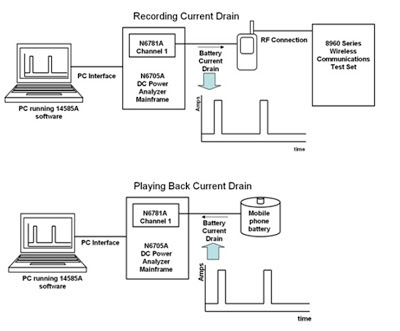

Let’s first look at the way existing USB charging work,

depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Legacy standard USB charging system

When the mobile device is connected to the USB adapter,

the mobile device first determines what kind of USB port it is connected to and

how much charging current is available that it will be able to draw in order to

recharge its battery. The mobile device then proceeds to internally connect its

battery up to the USB power through an internal solid state switch that

regulates the charging via the device’s internal battery management. However, a

major limitation here is the amount of available current and power. Today’s

mobile devices are using larger batteries. Up to 4 Ah batteries are commonly

used in smart phones and over 9 Ah capacity batteries are being used in

tablets. Even with later updates that increased the charging current to 1.5

amps for a dedicated charging port, this is a small fraction of the charging

current and power these larger batteries can handle. As one example, a 9 Ah

battery having a 1C recommended maximum charging rate equates to a 9 amp

charging current. This requires overnight in order to significantly recharge

the battery using standard USB charging.

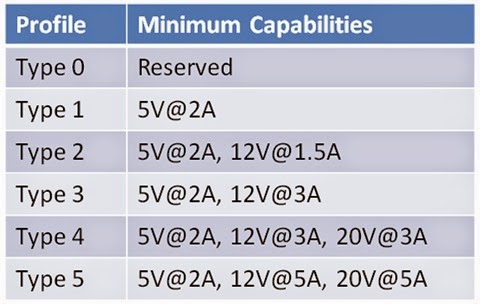

The shortcomings of legacy USB for battery charging

purposes has been well recognized and the USB Power Delivery 2.0 specification

has been released to increase the amount of power available to as much as 100

watts. This is accomplished by greater voltage, up to 20 volts, and greater

current, up to 5 amps. For a mobile device incorporating this, together with an

adaptive fast charging system, is able to charge its battery in much less time.

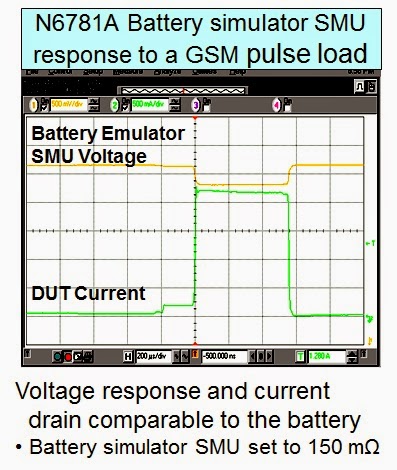

This set up is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: USB adaptive fast charging system

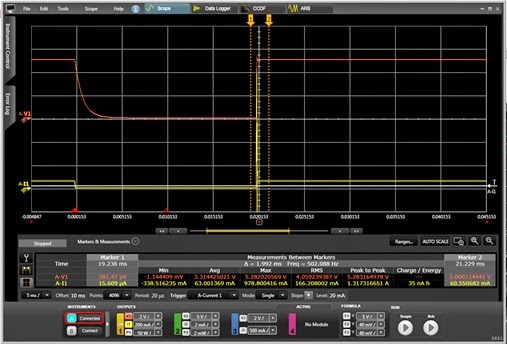

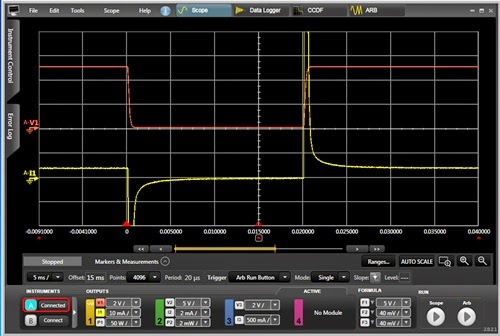

With adaptive fast charging, when the mobile device is

connected to the USB adapter, after determining that it has compatible fast

charging capabilities, it then negotiates for higher voltage and power. After

the negotiation the adapter then increases its output accordingly. A key thing

here is the mobile device will typically incorporate DC/DC power conversion in

its battery management system. Here it will efficiently convert the adapter’s

higher voltage charging power into greater charging current at a voltage level comparable

to the mobile device’s battery voltage, to achieve much faster charging. Now

you will be able to recharge your device over lunch instead of overnight!